A report from one of the country’s preemminent journalism schools has concluded that the news business as we know it is dead.

A report from one of the country’s preemminent journalism schools has concluded that the news business as we know it is dead.

That may not be a big surprise to many reporters, including the younger generation who did not grow up in the “all the news that’s fit to print” era and the older generation that has been kicked out the door and can’t find a job. But it’s a striking admission from a traditional J-school, the Columbia Journalism School, albeit from its New Age arm, the Tow Center for Digital Journalism.

“Post-Industrial Journalism: Adapting to the Present,” published last fall, is a long (126 pages) but fascinating read. Rather than bemoaning the past, the report faces reality and then looks at how we journalists can deal with it. “We have concluded that, no matter what model of subsidy the American journalism industry adopts, it will be unable to replicate the money generated by the mass-advertising subsidy of previous decades,” wrote Emily Bell, one of the report’s authors, in announcing its publication in the Columbia Journalism Review. In fact, the report admits in its introduction, “there is no such thing as the news industry anymore.” Rather than trying to figure out a new business model, as other reports on the state of the news business, not to mention every news organization in the world, are doing, the report focuses on how the craft of journalism is being revolutionized and what that means to practicing journalists.

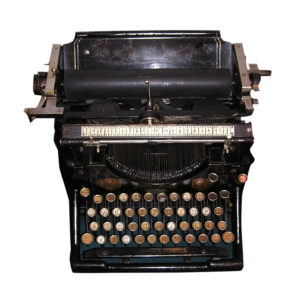

The report’s analysis of the collapse of the news business is dead-on. It describes how the journalism of the 20th Century had become essentially an industrial manufacturing business – it took people who typed words on paper and a printing press to build the product and a distribution system to sell it to consumers. In post-industrial journalism, digital technologies and the Internet have blown much of that model away.

But the authors insist that “there are many opportunities for doing good work in new ways.” What it takes, however, is an understanding of and appreciation for what journalists can do with these new technologies, unbound by the old, serial process of writing, editing, printing and shipping a final product. On the Internet, after all, stories live forever, and indeed can evolve and grow as time goes by. This new life of content is key and something that many news organizations haven’t figured out. “Content is endlessly reusable and should be designed for perpetual levels of iteration,” says the report. “News products will have to be made as reusable as possible: on other platforms, on other devices, in new news stories, even by other news organizations.” But some news organizations still frown on linking to other stories from other sources or providing additional resources, out of ingrained, Industrial Age habits that no longer hold.

The report tries to predict what the news environment will be like in seven years, 2020, at least the broad trends. It will be highly variable and dynamic, rather than the standard packages we still see today. “We’re not shifting from big news organizations to small ones, or from slow reporting to fast. The dynamic range of journalism is increasing along several axes at once.” We’ll see the newsrooms of large media companies shrink (further), a plethora of niche publications focused on narrow audiences, non-profit subsidies supporting journalism, public-supported reporting like National Public Radio, crowd-sourced news using Twitter, and citizen reporting. While everyone can be a reporter, there will still be plenty of room for the professional journalist because there will be so much demand for good, verified information as well as insightful analysis and interpretation of the news. “The Internet has unleashed demand for more narrative and more data-driven news, for a wider range of real-time sources and wider distribution of long-form pieces.”

All this is good news for freelancers as well as all journalists who are eager to explore this new world and experiment to see what’s possible. A good mantra for individual journalists, the authors say, is “Proceed until apprehended.” As the old structures topple, journalists are being freed from the chains of institutional journalism. Journalism is important, and the work of individual journalists is becoming even more important. In today’s world, individual journalists can not only be more important than their publisher, they can become their own publisher. “Far too much of the conversation of the past decade has assumed that the survival of existing institutions is more important than the ability of anyone to take on the sacred task

“The fate of journalism in the United States is now far more squarely in the hands of individual journalists than it is of the institutions that support them.” That’s tough for journalism institutions to hear, but it’s music to the ears of freelancers everywhere.